WR3 | Syllabus

Post-apocalyptic Fiction, Film, and Art

“Apocalypse, we propose, is never a locatable event but rather an imaginative practice that forms and deforms history for specific purposes: an aesthetic that does as much as it represents. Apocalyptic art may represent an imagined future, but it acts in and upon the present” (451).

— Jessica Hurley and Dan Sinykin, “Apocalypse: Introduction”

Course Description

Why do we feel such an attraction to disaster? Why do we produce novels, films, and other forms of art that contemplate the end of humanity? Scholars from many disciplines have offered theories about the appeal and meaning of such spectacles of apocalyptic destruction. We will read some of this critical literature, examining views from disciplines such as psychology, sociology, cultural studies, and religion. In addition to these assigned readings, each of you will engage in your own original process of inquiry on a related topic of your choosing. You will present your findings frequently to the community of scholars in our class, sharing and discussing your research discoveries and insights. Ultimately, you will produce a lengthy work of original scholarship that will contribute to this field of inquiry.

Health Information & Resources

Health & Wellness Information

Classroom Safety

- Please do not attend class if you have a fever, feel ill, or have any symptoms of COVID-19.

- If you succumb to a respiratory illness: please wear a mask and follow CDC guidance.

Course Policies

- If you miss class or a tutoring session due to illness, please email me to receive makeup information.

Health & Wellness Resources

- The Dartmouth College Health Service (primary care, counseling, wellness).

- If you would like to get vaccinated, find a shot near you.

Mental Health & Wellbeing Resources

The academic environment is challenging, our terms are intensive, and classes are not the only demanding part of your life. There are a number of resources available to you on campus to support your wellness, including:

- Your undergraduate dean

- The Counseling Center

- The Student Wellness Center

- The student-led Sexual Assault Peer Alliance (SAPAs)

Course Objectives

Writing 3 continues our focus on inquiry, critical thinking, and argumentation. The course additionally involves an introduction to academic research. Our libraries hold an impressive collection of traditional and electronic research tools as well as hundreds of thousands of books, journal articles, and assorted media. Navigating this ocean of information can be intimidating; however, excellent research skills are fundamental to your academic training. Therefore, we will spend a significant amount of time learning how to perform academic research and use our library resources effectively. By the end of this course, you should be able to do the following:

- Formulate research questions and keywords that may be used to guide a research process.

- Discover background information on a topic using reference materials.

- Locate books, periodicals, and other physical media within library collections.

- Locate electronic databases and query them with precision.

- Understand the importance of the process known as “peer review.”

- Critically evaluate sources for credibility and suitability for research.

- Use bibliographic software and a research journal to track and manage references.

- Craft a lengthy argument that contributes to an ongoing critical conversation.

Required Texts

- Open Handbook, by Alan C. Taylor

- Winter course readings may be found in Canvas.

Important Links

| Link | Purpose |

|---|---|

| No Silo | Course website, syllabus, readings, assignments, the Open Handbook. |

| Canvas | Submit assignments, course readings, view media. |

| Author Pages | A research archive built by our class (located in our Conspiracy! Google drive). |

| Tutor Zone | Resources for the 2-3 Tutor |

| The End | Random aphorisms on the (post)apocalyptic |

| FAQs | Frequently asked questions about the course |

Academic Honesty

All work submitted for this course must be your own and be written exclusively for this course. The use of sources (ideas, quotations, paraphrase) must be properly documented. Please read the Academic Honor Principle for more information about the dire consequences of plagiarism. If you are confused about when or how to cite information, please consult the course handbook or ask me about it before submitting your work.

| Since all work submitted for this course must be your own, the use of any artificial intelligence is not allowed. Any use of a LLM-based AI to brainstorm, outline, write, or edit assignments of any kind is an academic integrity violation. Similarly, students must read, summarize, and analyze our course readings without assistance from AI-derived technologies. These AI programs include, but are not limited to, bots like ChatGPT, Bard, and Claude or AI-based writing assistant tools like Grammarly, Quillbot, and WordTune.

If you have any questions about this policy or are not sure if a resource you have found will violate this policy, please ask me.

Attendance Policy

Regular attendance is expected. Bracketing religious observance, serious illness, or personal tragedy, no more than three unexcused absences in a single term will be acceptable for this course. This policy applies to:

- regular class meetings

- assigned X hours

- Tutor meetings

Four or more unexcused absences may result in repercussions ranging from significant reduction in GPA to failure of the course. If you have a religious observance that conflicts with your participation in the course, please meet with me beforehand to discuss appropriate accommodations.

| As I mention in the Health Information & Resources section above: if you are very ill, please don’t be a hero by dragging yourself into class to avoid an absence. I prefer that you consider the health of the others in our class and stay home if you have a fever or are possibly contagious. If you experience an illness or other human problem of the sort that exceeds three absences, I will definitely listen and try to work out something with you. Of course, this may not be possible if your emergency is so prolonged that it prevents meaningful participation and commitment to the course.

The Work of Reading

Before we meet to discuss a reading as a class, each of you should carefully read and critically engage the text on your own—interrogating, analyzing, and questioning the arguments, ideas, and assumptions you discover there. However, the work of reading in our course will also involve a series of complementary scholarly practices and habits, described below:

1. Annotate the texts . . .

As you read, I ask that you annotate the text—that is, mark up the text by adding meaningful symbols, marginal notes, and questions on the document itself. Note: this requires that you print out the text before you begin reading it. Bring this annotated copy of the reading with you to class to help you engage in the group discussion and analysis. There is no right or wrong way to mark up a text, but you should develop a system that you are comfortable with and try to stick with it. These annotations are flags to draw the attention of your future self to certain important features of a text at some later time. One key objective during annotation is to notice a text’s structure by flagging its main components—the thesis, argumentative claims, and pieces of evidence. As we try to understand these structural components of a piece of writing, we should also be evaluating and interrogating it. We can use the margins of the text to ask questions, make brief notes, indicate confusion, define unfamiliar terms, and make connections to other texts. This work serves two purposes: first, it helps you maintain a critical focus as you read; second, it helps you later if the text must be used for study or your own writing. If you plan on being successful in college, the ability to rigorously annotate texts is perhaps the most helpful and important skill you can develop.

| Further advice and caveats about annotation may be found in the “Annotation and Critical Reading” chapter of the Open Handbook.

2. Take critical notes . . .

After annotating a text, create an entry in your field notebook and take critical notes. Recent research reveals that taking notes by hand results in a significant boost to attention, brain activity, learning, and recall. In short, experiments show that students who take notes by hand are more successful than students who do so on computers.

I’d like you to give this a try; you may later decide to memorialize these notes in electronic form, either by retyping or scanning to .pdf. Take detailed notes on each of our course texts. Since you will write essays about these texts, these notes will be of significant help to you later. Your aims here should be to:

-

Reduce the entire argument to its bare essentials using paraphrase, summary, and selective quotation—carefully documenting page numbers during this activity.

-

Interrogate the text by asking questions, raising objections, and making observations.

-

Connect and compare the reading to other readings or ideas.

-

Define any unfamiliar terms or references.

-

Link the text to any outside research you perform.

At the end of this rigorous process you should have a simplified version of the essay as well as a number of critical observations, questions, and ideas that emerged in the process of reading.

| For more detailed information on the creation and purpose of these notes, read the chapter on “Critical Notes” in the Open Handbook.

3. Maintain a field notebook . . .

Your field notebook is a record of your thinking and observations, a chronicle of your attempts to know and understand. It should contain notes, ideas, and questions about our course readings, class discussions, and anything else that seems worth noting and remembering—even matters outside of our course. I like the metaphor of the field notebook as it conjures scenes of exploration, discovery, encounter, excitement, danger.

Keep a tight record of your mind’s travels.

Our objective for the field notebooks is to explore meaning, discover the argumentative structure(s) of our readings, evaluate supporting evidence, ask probing questions, connect to other readings, take notes, plan revision, and think critically. With luck, your notebook will become a central resource in our class discussions and an indispensable aid to you as you craft your essays. I’m providing these notebooks to you; if you fill yours up, just ask for another one.

| For more detailed information on the creation and purpose of these field notes, read the article on “Field Notes.”

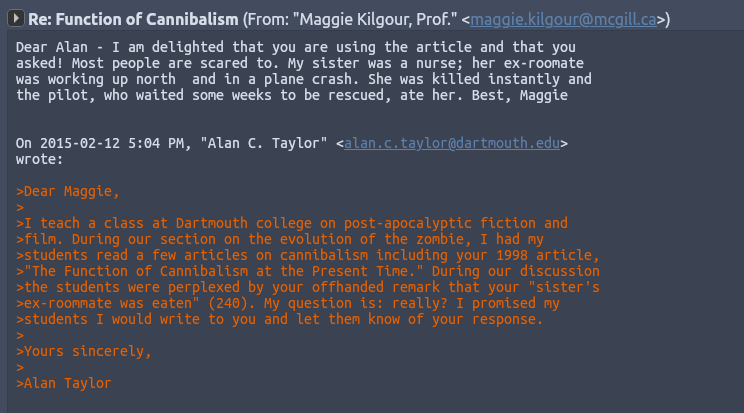

4. Micro research . . .

As you examine our assigned course readings, stay alert for anything that seems curious, unfamiliar, or unexpected—even if it sits at the margins of the text’s main purpose. When something catches your attention (an unfamiliar concept, an offhand reference, a gesture to history or biography, a questionable statement of fact) set the text aside and track down an explanation in the library. Write a short entry in your field notebook with a summary of your findings and the source(s) you used to make your discovery.

If you later think this bit of knowledge will be helpful or interesting to others, read or describe your entry during our class discussion of the text. In many cases, your efforts will serve to deepen our collective understanding of the text, since it will provide additional context for our reading. However, it may also be the case that your inquiry travels far, far away from the text to pursue some idiosyncratic and personal interest others might not fully appreciate or even understand. But you should follow the freak wherever it takes you.

This sort of work may feel rather counterintuitive at the start since it requires that you adopt a new approach to reading. Your schooling up to now has likely emphasized what we might call extractive or preparatory reading. In this mode, you move through a text strategically by highlighting key passages and building a mental picture of the text’s main arguments or ideas. While this approach is valuable, it treats the text as a mere container of information to be internalized and retrieved later (often for an exam or assignment) and measures success by how thoroughly you can reproduce or apply its contents. In distinction, these tiny research projects ask you to adopt a completely different attitude and posture toward the text—a far more subjective, personal, and creative one. In this mode of reading, the value lies not in mastering the content, but in discovering questions or problems that interest us personally. Reading becomes less a “digging down” or “drawing close” than it is a taking flight off to someplace unfamiliar and far away.

All research begins like this—not with a thesis or a topic, but in a recognition of ignorance. Something strikes us as curious or cryptic, and rather than merely passing over it, as we often do, we pause and consider it. This momentary hesitation is the origin of all inquiry. It marks the shift from passive reception to active pursuit. To research means to go looking or hunting for something—to follow a trail out of the text and into the library, the archive, the database, the field. These small research assignments will help get us in the habit of drawing out these pauses rather than skipping over them, hopefully developing a research habit or reflex in the process.

Grading

“Grades teach students that others are the only judge. Students finish the assignment, forget about it, and hope for the best. They learn to please: “What does this professor want?” They learn that someone, somewhere, will tell them if they are any good” (139).

—Susan Blum, I Love Learning; I Hate School: An Anthropology of College

A few years ago I decided to quit grading, mostly as an emergency response to the realities of teaching during the COVID pandemic. Although I didn’t know it at the time, a large body of research concludes that grading is not just counterproductive, but actively harmful to the process of education. As Jesse Stommel writes, grades are “not a good measure of learning, they inhibit intrinsic motivation, and they create a competitive environment between students and hostile relationships between students and teachers.” Perhaps the foremost scholar on grading, Alfie Kohn, argues that grading produces three predicable effects in students: “less interest in learning, a preference for easier tasks, and shallower thinking” (xiv). If you think back on your experiences in high school, you may very well discover evidence of these effects in your own life.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

For the reasons described above (and others we will explore together), this class will not feature traditional letter grades for evaluation. To be sure, I will give you feedback and encouragement and promise to assist you in any way that I can. I will ask a lot of questions and try to push you to experiment and grow as a writer. You will receive similar feedback from your colleagues in the class. And you will also perform reflective self-evaluations of your writing, thinking, and effort. But at no point will this complex and important work be reduced to a percentage or letter grade.

At the end of the term we will reflect together on your progress, effort, participation, and performance; we will decide together what final grade to enter into Banner. This discussion about your performance in the class will involve our mutual reflection on the following topics:

- Participation

- Attendance

- Collaboration and sharing

- Late, incomplete, missing work

- Growth

- Effort

| There is one important caveat. To earn this right (and to pass the course), all assignments must be completed and a solid attendance record must be kept.

Major Assignments

1. Formal Research Essay

You will write one formal research essay. The project will likely involve many of the core competencies we developed in the previous term including argumentation, critical thinking, close reading, synthesis, and theoretical analysis. You may write on any topic you wish, so long as it is a contribution to our course conversation and theme. Please discuss your ideas with me before you get too far along. I am happy to meet with each of you to discuss ideas and help formulate a research plan.

Essay requirements:

The essay must be submitted in the Chicago format.

It must contain a minimum of 15 peer-reviewed sources.

Sources that are not peer-reviewed may also be used. However, be judicious if you do so.

Your essay should be at least 3,700 words, or about 15 pages in length.

2. Research Workshops

Several workshop assignments will help you gain confidence with using library resources, constructing bibliographies, and managing large research projects.

3. Author Page

Each of you will curate a webpage dedicated to your research project. We will call this site your Author Page. You may create this page as a shared Google Doc or use the Dartmouth Journeys platform. After creating your page, link to it on the course research projects page so that we may locate it. Make sure to share the document by choosing Share > General access > Dartmouth College. We will use these Author Pages to view your project as it evolves over time. One of your most important responsibilities this term is to keep this page updated. Your author page should contain the following:

- a short research proposal/statement of no more than 250 words.

- a running list of the keywords and subject headings you are using to search for sources.

- an

annotated bibliographyof all the sources used to construct your research project.- Use permalinks to link your sources to their location online in the library system.

- a current draft of your research essay.

- a weekly reflective “blog” post about the progress of your research project.

I have created a model author page here that you may use as a template.

4. End-of-Week Reflection

Compose a weekly reflective “blog” post on your Author Page that details your efforts that week to further your research project. At first these posts will likely be searching, inarticulate musings as you fumble through possible ideas for a research project. However, as your research intensifies and comes into sharper focus, these posts should begin to include the specific steps that you took that week to further the project in some way. What kind of research problems or difficulties did you encounter? What sources did you locate? How is the project evolving as you read and think more deeply on your subject? In essence, I would like you to blog your experiences as a novice researcher engaged in your first big research project. Significantly: the things you say in your posts will help me, the tutor, and your colleagues as we try to assist you with your project.

5. Presentations

You will make one formal presentation at the conclusion of the term to explain your research project to our class. You will also make a number of informal presentations about your ideas, research, and writing as they evolve over the term. These informal presentations may not be announced, so be prepared to discuss your project at any time.

6. Noticing Project

Throughout this term we will each engage in a small research project that we’ll call our noticing work. The objective of this work is to practice deep observation and slow looking by returning repeatedly to a single location on or near campus and observing whatever there is to see. This assignment asks you to cultivate attention, to notice both change and constancy, and to document what emerges when you challenge yourself to truly and patiently look.

Help With Your Writing

There are many sources of help for your writing assignments. I am happy to meet with you all term during my office hours or by appointment. Each of you will meet with our tutor for 45 minutes per week to go over your writing and plan revision. If you require further help, the Writing Center offers excellent peer tutoring on all phases of the writing process—from generating ideas to formal citation.

Students With Disabilities

Students requesting disability-related accommodations and services for this course are required to register with Student Accessibility Services (SAS; Getting Started with SAS webpage; student.accessibility.services@dartmouth.edu; 1-603-646-9900) and to request that an accommodation email be sent to me in advance of the need for an accommodation. Then, students should schedule a follow-up meeting with me to determine relevant details such as what role SAS or its Testing Center may play in accommodation implementation. This process works best for everyone when completed as early in the quarter as possible. If students have questions about whether they are eligible for accommodations or have concerns about the implementation of their accommodations, they should contact the SAS office. All inquiries and discussions will remain confidential.

Symbol Legend

| Symbol | Note |

|---|---|

| Student presentations | |

| Homework | |

| In-class work | |

| A new major assignment | |

| Workshop assignment | |

| Assignment due | |

| Print out work and bring to class | |

| Peer work, in pairs or groups | |

| Discussion topic | |

| In-class lecture | |

| Course reading download (.pdf) | |

| Learn something new | |

| Question of the day™ | |

| Friday Soap Box | |

| Film | |

| Audio lecture | |

| Micro Research work | |

| Noticing Work Projects | |

| Research progress checkup |

Schedule of Readings and Assignments

1 - Course Introduction

Monday, 1.5

In-class work

- Question of the Day™

- Class reunion, course overview, syllabus tour, housekeeping matters.

Wednesday, 1.7

Homework

-

Introduction to Academic Research| A brief introduction to the processes involved in a research project. The lectures and workshops that follow build on this initial description.

In-class work

- Question of the Day™

- Review the Introduction to Academic Research reading.

- Discuss reading.

Friday, 1.9

Homework

- Sontag, Susan. “The Imagination of Disaster.” Commentary, vol. 40, 1965, pp. 42–48.

- Print out, read, annotate, and take critical notes on the reading in your field notebook.

- Make a Micro Research entry in your field notebook.

- In your field notebook, make a list of any film, television show, or work of literature in the apocalyptic genre that you find interesting or memorable.

In-class work

- Friday Soapbox

- Discuss reading and possible research ideas

2 - Introduction to Library Research

This week we will continue our overview of library research, learning some basic skills for querying catalogs and databases. We will also learn about a form of analysis known as cultural studies (much of our course and its readings are inspired by this breed of criticism).

Monday, 1.12

Homework

-

Searching with Precision| Watch the video and study the information on searching with precision. - Choose your Noticing Work location or subject and begin your observations.

In-class work

- Question of the Day™

- Lecture: Searching with Precision.

-

Workshop 1: Searching with Precision| This workshop will help you learn how to query databases and catalogs with precision, saving you time and headaches.

Wednesday, 1.14

Homework

-

Finding Periodicals & Electronic Databases| Read about periodicals and electronic databases. We will do the workshop portion in class.

In-class work

-

Workshop 2: Finding Periodicals & Electronic Databases| This workshop will help you learn how to locate online periodicals (such as scholarly journal articles). - Discuss lecture and do workshop.

Friday, 1.16

Homework

-

Introduction to Cultural Studies| This class will frequently use a mode of analysis associated with cultural studies. This audio lecture provides a brief introduction to this form of inquiry/analysis.

In-class work

- Question of the Day™

- Discuss lecture.

Due

- Create a barebones Author Page and link to it on our research projects page.

- Submit an end-of-week reflection to your Author Page.

3 - Apocalypse & the State of Nature

Philosophers and social scientists have attempted to explain the origins of civilization and the rise of the modern state for centuries. A key concept in this conversation is the “state of nature,” a hypothetical condition where human beings lived without government. In this primitive state there is no law or authority, only anarchy and the pervasive threat of violence. Thinkers of the past such as Hobbes and Locke used this hypothetical condition to explain why the state of nature no longer exists and how civilized orders came to be. Today, however, many writers, filmmakers, and social scientists imagine apocalyptic scenarios of disaster wherein society regresses again to chaotic states of nature. Why do we produce such imaginings? What purpose(s) do they serve? And why have these narratives become so prominent of late?

Monday, 1.19

- Martin Luther King Day. No classes. We will use the X-hour this week.

- Continue your Noticing Work.

Tuesday, 1.20 (X-hour session)

Homework

- Thomas Hobbes, selection from Leviathan (1651).

- Print out, read, annotate, and take critical notes on the reading in your field notebook.

- Make a Micro Research entry in your field notebook.

In-class work

- Question of the Day™

- Discuss reading.

-

Workshop 9: What is Peer Review?| This workshop helps you understand the purpose of peer review and how to recognize peer-reviewed articles and books.

Wednesday, 1.21

Homework

- Claire Curtis, Post-Apocalyptic Fiction and the Social Contract, “Introduction.”

- Print out, read, annotate, and take critical notes on the reading in your field notebook.

- Make a Micro Research entry in your field notebook.

-

Finding Books and other Physical Holdings in the Library| Study the portion about finding books and other items in the library stacks; we will complete the workshop portion in class.

In-class work

- Question of the Day™

- Discuss reading.

-

Workshop 3: Finding Books and other Physical Holdings in the Library| This workshop will help you learn how to locate physical items in the library’s stacks.

Friday, 1.23

In-class work

- Friday Soapbox.

- Discuss reading.

- Research progress checkup.

Due

- Submit an end-of-week reflection to your Author Page.

- Submit work for Workshop 3.

4 - The Apocalypse & the Other I

Cultural Studies scholars argue that post-apocalyptic narratives proliferate during periods of social crisis. During these moments of extreme social stress, cultures transmute fear, anxiety, or dread into popular art forms such as novels or films. Thus, by examining popular media produced during these particular historical moments we are afforded a glimpse of how a culture worked through difficult social problems, reacted to challenges to its foundational values, and related to its various “Others.” In this section we will examine two films, The Last Man on Earth (1964) and I Am Legend (2007), both adaptations of Richard Mattheson’s 1954 novel I Am Legend. What cultural anxieties or problems do these films articulate? What social solutions do they seem to offer? Significantly, how do the differences between these two films provide a metric for measuring the evolving concerns of America from the 1960s to today?

Monday, 1.26

Homework

- Film, The Last Man on Earth (1964) | Film is in the “Panopto Video” section of Canvas. Resist the urge to watch the film at faster than 1x speed.

- Wikipedia page on the 1960s | Skim this reading to gain an overview of the important historical/cultural events in this decade.

- View and take critical notes on the film in your field notebook.

- Stills from The Last Man on Earth.

- Continue your Noticing Work.

In-class work

- Question of the Day™

- Discuss film.

Wednesday, 1.28

Homework

- Robin Wood, “The American Nightmare”

- Print out, read, annotate, and take critical notes on the reading in your field notebook.

- Make a Micro Research entry in your field notebook.

In-class work

- Question of the Day™

- Discuss reading.

-

Workshop 7: Bibliographic Software / Research Journal| Over your career as a student and a professional you will encounter and make use of thousands of books and articles and assorted media. Many of these texts will be very useful to you later, if you take the time to save and organize them now. There is an app for that.

Friday, 1.30

In-class work

- Friday Soapbox.

- Discuss film, reading.

- Research progress checkup.

-

Workshop 4: Works Cited or Bibliography| This workshop will help you gain familiarity with constructing a Chicago style bibliography for a research paper or project.

Due

- Author Page: research proposal (250 words), annotated bibliography of current research.

- Submit an end-of-week reflection to your Author Page.

5 - The Apocalypse & the Other II

Monday, 2.2

Homework

- Film, I Am Legend (2007)

- View the film and take critical notes on in your field notebook.

- Alternate ending of I Am Legend (only watch after completing the original film).

- Continue your Noticing Work.

In-class work

- Question of the Day™

- Discuss film.

Wednesday, 2.4

Homework

- Nope!

In-class work

- Question of the Day™

- Discuss film.

-

Workshop 5: Cutting Corners in Research| The best researchers know how to cut corners and work efficiently. This lecture presents you with some tips that will save you time. -

Workshop 6: "Getting Sh*t the Library Doesn't Have"| As a researcher you will encounter many problems, but one of the most annoying is discovering that some other person has rudely checked out your book. Sometimes our library doesn’t own a book or article that you want to read. What do you do when these things happen? You have many options that won’t cost you a dime.

Friday, 2.6

In-class work

- Friday Soapbox.

- Discuss film.

- Research progress checkup.

Due

- Update research proposal and annotated bibliography on your Author Page.

- Submit an end-of-week reflection to your Author Page.

6 - The Zombie, Civil Rights, & Race

“[T]he true subject of the horror genre is the struggle for recognition of all that our civilization represses or oppresses.”

—Robin Wood

Vampires, werewolves, and Frankenstein are all monsters of European extraction; the zombie, however, was made in America. This prompts several questions: Why was the zombie born here rather than someplace else? What is it about the Americas and their history that made the figure of the zombie possible and popular? What does it say about us and our culture that we have created precisely this type of monster? In this section we will attempt to answer these questions by tracing the evolution of the zombie—from its origins in the slave-based plantation cultures of the Americas through modern interpretations of the figure in contemporary literature and film. Significantly, the zombie of today differs markedly from its precursors in the cinema of the 30s, 40s, and 50s. In these earlier films the zombie was a figure within an imperialist discourse that expressed racist ideologies and the anxieties of post-slavery cultures throughout the Americas. However, just as the figure of the zombie had nearly been forgotten, a new form of the creature appeared in 1968 in George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. No longer was the zombie a folkloric figure born of the struggle between master and slave; now it was a cannibalistic creature that stalked the countryside in swarms, mindlessly searching for human flesh. How do we account for this sudden transformation of the zombie? What cultural “work” did the zombie perform?

Monday, 2.9

Homework

- Film, Night of the Living Dead (1968)

- Continue your Noticing Work.

In-class work

- Question of the Day™

- Discuss film.

Wednesday, 2.11

Homework

- Peter Dendle, “The Zombie as Barometer of Cultural Anxiety.”

- Maggie Kilgour, “The Function of Cannibalism at the Present Time.”

- Print out, read, annotate, and take critical notes on the reading in your field notebook.

- Make a Micro Research entry in your field notebook

In-class work

- Scene from White Zombie (1932) at Murder Legendere’s plantation

- Question of the Day™

- Discuss film and reading.

Friday, 2.13

Homework

- Complete your essay draft.

In-class work

- Friday Soapbox

- Peer Review: During class time today you will meet with two of your colleagues to perform peer review.

-

Lecture: Managing Large Research Projects| How do you begin when you’ve collected a large pile of books and articles that will be parts of your research project? Often, a large collection of sources leaves you feeling paralyzed. This lecture gives you some ideas about how to process your research and start writing.

Due

- Update research proposal and annotated bibliography on your Author Page.

- Submit an end-of-week reflection to your Author Page.

- Research Essay Draft I (3-5 pages).

7 - Slow Violence, Eco-pocalypse, and Poverty

Monday, 2.16

In-class work

- Question of the Day™

- The Chicago Style

Wednesday, 2.18

- Bonus Office Hours 11:30—3:00

Friday, 2.20

8 - TEOTWAWKI: Prepping for the End

Recent years have seen an explosion of “reality” television programming based in survival skills or challenges. Popular shows in this regard include game shows like Survivor and adventure shows like Man vs. Wild and Survivorman. Newer programming includes the Discovery Channel’s Dude, You’re Screwed, Alaska Bush People, Dual Survival, and the rather prurient Naked and Afraid. While these shows give viewers the vicarious thrill of braving the wilderness from the comfort of their armchairs, there has recently been an explosion in survivalist subcultures, known collectively as “prepping.” Preppers build bomb shelters and other fortifications where they stockpile food, supplies, firearms, and ammunition in preparation for TEOTWAWKI: The end of the world as we know it. A number of “reality” television shows have emerged in response to these cultural phenomena: Doomsday Preppers, Doomsday Castle, and Doomsday Bunker. The list of prepper fears is long: generalized civil unrest, total social collapse, global weather catastrophes, the return of Christ, peak oil, attacks using EMPs, solar flares, and, of course, zombies. Are these views largely fueled by paranoia or a desire for self-reliance? Do these fears and anxieties signify some larger, unarticulated criticism or anxiety about modernity, democracy, or capitalism?

Monday, 2.23

Homework

- Doomsday Preppers.

- “The super-rich ‘preppers’ planning to save themselves from the apocalypse”.

- Print out, read, annotate, and take critical notes on the reading in your field notebook.

- Continue your Noticing Work.

In-class work

- Question of the Day™

- Discuss film and reading.

Wednesday, 2.25

Homework

- Bradley Garrett, “Doomsday Preppers and the Architecture of Dread”.

- Make a Micro Research entry in your field notebook.

In-class work

- Question of the Day™

- Discuss reading.

Friday, 2.27

In-class work

- Friday Soapbox

- Peer Review: During class time today you will meet with two of your colleagues to perform peer review

- On Introductions.

- Discuss research proposals

Due

- Update research proposal, annotated bibliography, paper draft on your Author Page.

- Submit an end-of-week reflection to your Author Page.

- Research Essay Draft II Due (7-10 pages).

9 - Drafting, Revising, Presenting

This week is dedicated to our presentations. Each of you will make a short presentation around 5 minutes in length. Your presentation may take any form you like, but consider your audience. Your fellow classmates have not read your essay or researched your topic. How can you help them understand your ideas and arguments? What context will they need to know? What terms or historical details do you need to unpack? Make sure to practice and time your talk so that you don’t go over the allotted time. Feel free to use a visual aid, such as PowerPoint slides or handouts.

- Each of you should be prepared to present on Monday. I will have my son Amos randomly number you to avoid any appearance of favoritism. He will get to practice his numbers as a result!

Monday, 3.2

In-class work

Wednesday, 3.4

In-class work

Friday, 3.6

In-class work

- Eat celebratory donuts!

- Tearful goodbyes.

- End-of-term Reflection and Self-Assessment.

Due

- Submit an end-of-week reflection to your Author Page.