Field Notes

Another value of field notebooks is their ability to serve as an incredibly fertile incubator for your ideas and observations. By jotting down interesting observations, questions, and miscellaneous ideas, your field notebook can serve as a powerful catalyst for new experiments and projects.

Our notes should, indeed, be useful for purposes of review; yet that usefulness is not their chief value. . . . The practical value of our notes will take care of itself as a matter of secondary importance, if we devote ourselves wholly to their main purpose—to make us alert, clear-headed, and responsible . . . . To take good notes is not preliminary to study, but study itself of the most vital kind; calling at once on all one’s powers of concentration, judgment, and craftsmanship.

I will describe here a special kind of journal which I call a dialectical notebook. I like to remind myself (and others) that dialectic and dialogue are closely related; that thinking is a dialogue we have with ourselves; that dialectic is an audit of meaning—a continuing effort to review the meanings we are making in order to see further what they mean. The means we have of doing that are—meanings. The dialectical notebook keeps all our meanings handy. Here is how it works: the dialectical notebook is a double-entry journal with the two pages facing one another in dialogue. On one side are observations, sketches, noted impressions, passages copied out, jottings on reading or other responses; on the facing page are notes on these notes, responses to these responses—in current jargon, “meta-comment.” The first thing the dialectical notebook can teach us is toleration of those necessary circularities. Everything about language, everything in composing, involves us in them: thinking about thinking; arranging our techniques for arranging; interpreting our interpretations.

— Ann Berthoff, “Dialectical Notebooks and the Audit of Meaning”

Thoughts one achieves in one’s final draft cannot be articulated at first. They are only reached via a series of intermediate externalized thoughts. Paper can be like a conversation partner, but with the enhancement that the words do not dissolve into the air. What is written can also be taken up by someone else who does, as it were, the backward translation of words into mental models within which he or she can think. In this way, thought can be passed from mind to mind. Also the writer can be the reader, can replay an externalized thought in language form back to himself or herself, and take part in the iterated movement by which thoughts can be improved.

Writing doesn’t lay out the notions that are lying dormant in the mind waiting to be displayed. Writing is the “seeing into” process itself. It is the tearing through the mind’s concepts. The process itself unfolds truths which the mind then learns. Writing informs the mind; it is not the other way around. Insights resulting from writing, whether about the building of a better chicken coop or about the nature of man, once written become the property of the mind and then in turn need, for the writer’s future development, to be bypassed or set aside, so as to allow room for new insights. The mind (that is, our consciousness) receives and parrots; it does not generate new cognition or insights.

— Barrett Mandel, “Losing One’s Mind: Learning to Write and Edit.”

What are field notes?

Field notebooks have been used by explorers and scientists for centuries to aid in observation, reflection, and preservation. They are records of human attempts to know and understand: chronicles of adventure and discovery in unexplored territories, descriptions of radical otherness and cultural difference, narratives of danger and fear, stories of deeply personal change and evolution. They are also jottings of the most mundane sort: ordinary facts, passing thoughts, offhand queries, bits of data, placeholders for further study—even a weird fantasy about a little bird that keeps repeatedly building a nest on your house. We will use the conceit of entering the field as a way of understanding our work together in this class. I like how the metaphor of fieldwork conjures scenes of exploration, discovery, danger, and transformation—experiences that I have come to associate with education and the work of learning.

This term we’ll be keeping all of our course notes, thinking, inquiry, and planning ideas inside a notebook—likely a series of them. When you have an idea, a passing thought, when you discover an interesting quotation from a reading, when you detect a connection between our class and something outside of it, when you create an outline for your upcoming draft or receive some good advice from our teaching assistant, I want you to put it in this book. When you think of this class—of the work of this class—I want you to think of your field notes.

In this class, the field notes are the work.

Observation

The field notebook is a technology of observation and intentional curiosity. Much like a naturalist or sociologist uses a field notebook to document the phenomena they study, we will use our notebooks to record observations, ideas, feelings, and responses as they occur in time. By copying out bits of text that seem important to us, and by jotting down spontaneous thoughts, insights, and questions as we have them, we gather raw materials for a more structured analysis in the future. The field note invites slow looking and careful description, a sort of meditation typified by an openness to experience and the deferral of interpretation. As we encounter readings, the thoughts of others, responses to our writing—as we go about our lives as unique human beings—what do we notice?

Reflection

The field notebook is a tool for reflection. When we preserve an artifact in our field notes it becomes available for future reflection, analysis, connection. Revisiting these notes allows us to engage in a continuous process of re-evaluation and refinement, incorporating new insights and information as they arise by entering into a dialogue with our previous entries. This iterative approach facilitates deeper understanding, allowing us to reassess our initial interpretations and adapt our ideas in light of new perspectives or evidence. The field notebook thus becomes a space for experimentation, for viewing matters from different perspectives, for solving complex problems, and for slowly accreting ideas and evidence until they form understanding and arguments. By regularly returning to our field notes, we will engage in a systematic process of idea development, enhancing our ability to think critically and adapting our writing based on an ongoing process of discovery and reflection.

Writing Process

Field notes are an essential intermediary step in the process of writing. Some compelling cognitive science research shows the critical importance of these sorts of records as preparation for future, more formal, writing. Notes such as these essentially accomplish the “freezing” of thoughts, ideas, or selected text passages which helps us deal with the central problem of writing: cognitive overload. Since our brains cannot hold the entirety of an argument or the full text of something we are working on, the encoding of these thoughts on the page frees up our brains to perform other, higher-level cognitive tasks. We can leave, return, connect, and reevaluate ideas and texts only once they are manifested on the page.

Staying in Touch

The field notebook is a way of staying in touch with who we used to be. While field notebooks aid our explorations of the external world, they may also be used to perform an archeology of the self. We may choose to preserve experiences or thoughts that are not strictly concerned with our coursework—recordings of everyday events and facts about our lives. We might preserve a song lyric, a dream, an observation about a close friend. Or we may choose to make entries on a personal struggle or record a feeling of loss or disappointment that shattered us. Sometimes we may have no idea why we decide to preserve certain things, much as we might have the sudden urge to save a pebble from a stream and place it wet and glistening into our pocket. Why might we do this sort of collecting? In her essay “On Keeping a Notebook,” Joan Didion says that ultimately she keeps a notebook to “Remember what it was to be me: that is always the point.” Years from now you will have forgotten nearly all of your experiences in college; all that will remain is a blur of faces, some embellished stories, and perhaps a handful of regrets. Unless, of course, you take the time to save some pebbles now.

- Possibly related: there is also several decades of compelling research showing that personal journal writing helps relieve anxiety, depression, and other stress-related disorders. Obviously, for the sake of privacy, you might choose to put more personal thoughts in a separate notebook.

How to Set up your Field Notebook

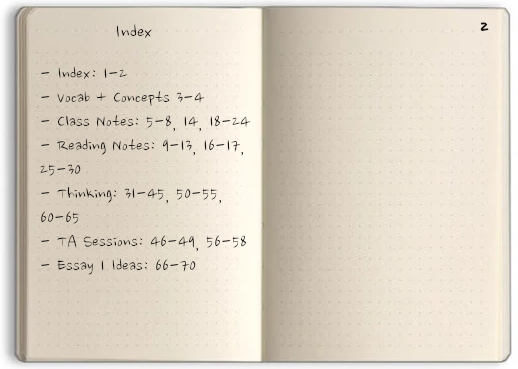

- Begin each new notebook with a two-page spread for use as an index.

- Follow the index with a two-page spread for new vocabulary and concepts.

- Number each page for ease of reference.

- Update your index after making entries.

- Begin each entry with a timestamp of some kind, such as this

YYYYMMDD, or 20241028.

Bibliography on Handwriting Research

Popular literature

-

Hu, Charlotte. “Why Writing by Hand Is Better for Memory and Learning.” Scientific American, 1 May 2024, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-writing-by-hand-is-better-for-memory-and-learning/.

-

May, Cindi. “A Learning Secret: Don’t Take Notes with a Laptop.” Scientific American, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/a-learning-secret-don-t-take-notes-with-a-laptop/.

-

Kirsch, Melissa. “How to Slow Down.” The New York Times, 24 Sept. 2022. NYTimes.com, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/24/briefing/field-sketching-slowing-down.html.

Academic literature

-

Allen, Mike, et al. “Is the Pencil Mightier than the Keyboard? A Meta-Analysis Comparing the Method of Notetaking Outcomes.” Southern Communication Journal, vol. 85, no. 3, May 2020, pp. 143–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/1041794X.2020.1764613.

-

Alonso, María A. Pérez. “Metacognition and Sensorimotor Components Underlying the Process of Handwriting and Keyboarding and Their Impact on Learning. An Analysis from the Perspective of Embodied Psychology.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 176, Feb. 2015, pp. 263–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.470.

-

Berthoff, Ann. “Dialectical Notebooks and the Audit of Meaning.” The Journal Book: For Teachers in Technical and Professional Programs, edited by Susan Gardner and Toby Fulwiler, Boynton/Cook Publishers, 1999, pp. 11-18.

-

Canfield, Michael R. Field Notes on Science & Nature. Harvard University Press, 2011. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674060845.

-

Gortner, Eva-Maria, et al. “Benefits of Expressive Writing in Lowering Rumination and Depressive Symptoms.” Behavior Therapy, vol. 37, no. 3, Sept. 2006, pp. 292–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2006.01.004.

-

Krpan, Katherine M., et al. “An Everyday Activity as a Treatment for Depression: The Benefits of Expressive Writing for People Diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder.” Journal of Affective Disorders, vol. 150, no. 3, Sept. 2013, pp. 1148–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.065.

-

Korte, Satu-Maarit, and Minna Körkkö. “Embodied Learning with and through Different Writing Methods.” Embodied Learning and Teaching Using the 4E Cognition Approach, by Theresa Schilhab and Camilla Groth, 1st ed., Routledge, 2024, pp. 54–62. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003341604-9.

-

Mandel, Barrett J. “Losing One’s Mind: Learning to Write and Edit.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 29, no. 4, 1978, pp. 362–68. https://www.jstor.org/stable/357021

-

Mangen, Anne, and Lillian Balsvik. “Pen or Keyboard in Beginning Writing Instruction? Some Perspectives from Embodied Cognition.” Trends in Neuroscience and Education, vol. 5, no. 3, Sept. 2016, pp. 99–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tine.2016.06.003.

-

Mueller, P. A., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2014). “The Pen Is Mightier Than the Keyboard: Advantages of Longhand Over Laptop Note Taking.” Psychological Science, 25(6), 1159-1168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614524581

-

Oatley, Keith, and Maja Djikic. “Writing as Thinking.” Review of General Psychology, vol. 12, no. 1, Mar. 2008, pp. 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.12.1.9

-

Pennebaker, James W., and Cindy K. Chung. “Expressive Writing: Connections to Physical and Mental Health.” The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology, edited by Howard S. Friedman, 1st ed., Oxford University Press, 2012, pp. 417–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195342819.013.0018.

-

Van der Weel and Van der Meer. “Handwriting but not Typewriting leads to Widespread Brain Connectivity: a High-density EEG Study with Implications for the Classroom.” Frontiers in Psychology. Vol. 14, 2024. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1219945

-

Vasylets, Olena, et al. “The Role of Cognitive Individual Differences in Digital versus Pen-and-Paper Writing.” Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, vol. 12, no. 4, Dec. 2022, pp. 721–43. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2022.12.4.9.

-

Wilhelm, Kay, and Joanna Crawford. “Expressive Writing and Stress-Related Disorders.” The Oxford Handbook of Stress and Mental Health, by Kay Wilhelm and Joanna Crawford, edited by Kate L. Harkness and Elizabeth P. Hayden, Oxford University Press, 2020, pp. 704–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190681777.013.34.